I’m spending more time on tanglad.tumblr.com. And I’m looking for fellow Pinoy kasamas on tumblr. Mag-hello naman kayo.

I’m reading Neferti Tadiar’s Things Fall Away, and this passage leaps out:

I’m reading Neferti Tadiar’s Things Fall Away, and this passage leaps out:

…one of my man objectives in this book has been to carefully attend to the varied, creative potential of subjective practices that socially oriented and social movement literatures attempt to figuratively capture and yet tend to diminish in the fabulation of proper historical subjects. Often viewed a atavistic and mystified habits and therefore as forms of weaknesses and self-oppression that need to be overcome, these devalued, supplemental experiential practices nevertheless importantly create and transform the very material, social structures in which feminists, urban activists, and revolutionary forces actively seek to intervene…. Such diminished experiences have helped to bring about broad social changed in ways that these groups could not foresee. (p 8., emphasis mine)

Tadiar labels these diminished experiences as things that “fall away” from capitalism, activities that are productive but not in the ways that are prescribed and recognized by neoliberal capitalism. Like performance. Art. Indigenous women’s labor collectives and seedbanks. Movement, and being outside.

But I’m struck too at how she includes activists, feminists, revolutionary forces among those who diminish such “fall away” experiences, especially when they’re not easy to reconcile with what is seen as the “proper” historical subject. Because it is easy for someone like me to speak for masa in solidarity, to find that a peasant community’s struggle for for a health clinic and the struggle for land reform are equally important. They might not be, for the peasants who are still without healthcare.

I’m reminded of an argument with a friend, who patiently listened to me rant about Catholicism and false consciousness, opium, etc. She then reminded me that Liberation Theology could not have been foreseen by non-Catholics, or even by former Catholics like me. It’s a theology of faith, love, freedom, and revolution that could only have been nurtured in this specific community, a community that I had arrogantly dismissed.

I’m still struggling through Things Fall Away, and with questions of how to conduct ethical dialogues and coalitional research. Especially since I will soon be embarking on ethnographic research, and its easy to fall into the trap of thinking of oneself as an ally who could speak for people in a marginalized community. The researcher who does that will never even be aware of the experiences that she will miss, of the great possibilities that could just fall away as a result.

Posted in Good reads, Philippines | Tagged Neferti Tadiar, Philippines, Things Fall Away | Leave a Comment »

A friend described cycling as a whitestream activity. I mentioned that I saw a lot of poc commuters in the early morning, and expect more as Los Angeles Metro fares go up once again (boo!). But that’s commuting, she said. Of course there would be a lot of poc. Riding a bike becomes “cycling,” a sport or a recreational activity, when you don’t depend on it to get around. Much the same way that walking becomes “hiking.”

She may have something there. After a year of riding, it’s still a nice surprise every time I see other people of color on the trail. There’s a Pinoy group, and a few Pinoy friends and family who ride with me when they can, but mountain biking (and trail running, I think) still seems pretty whitestream. And the less I dwell on the mountainbike boards, where a post asking “Any Pinoy riders in SoCal?” was met with a flurry of “I’m forming a whites-only riding group” posts and charges of “reverse racism,” the better for my sanity.

I snicker at claims that modern mountain biking was born in the 1970s, when a bunch of NorCal dudes started downhilling Mt. Tam and when road bike companies started manufacturing mountain-specific bikes. As a kid in the Philippines, my partner M used to ride his bike in the fields behind his house. It wasn’t called mountain biking then, of course. Just a bunch of kids riding their bikes where they could, like countless kids have been doing since bikes were invented. But that probably doesn’t count as modern mountain biking. Or as mountain biking, for that matter.

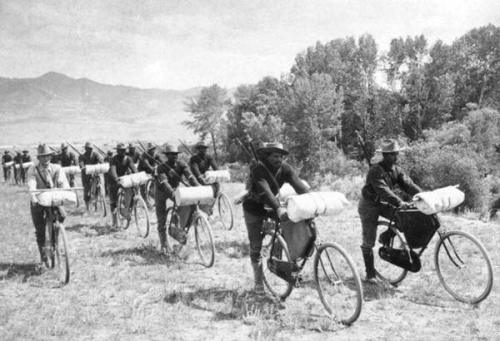

Neither was it called mountain biking in 1896, when 20 Buffalo Soldiers from the 25th Infantry rode from Fort Missoula, rode to St. Louis, Missouri. This wonderful picture makes me happy:

And they rode wagon trails through the Rockies on steel singlespeeds that weighed about 70 lbs (including gear). Damn. POCs on mountain bikes rule.

Posted in outdoors, race | Tagged buffalo soldiers, mountain bike, mountain biking | 2 Comments »

(Part One)

The following quote is from Dylan Rodriguez’s article “The Condition of Filipino Americanism: Global Americana as a Relation of Death”: [pdf]

At the nexus of a prevailing Filipino American discourse that celebrates the Filipino-American as a cooperative participant in the United States nation-building project sits an “unnamable violence” that masks the genocidal preconditions of “multiculturalist white supremacy to which this discourse unwittingly subscribes…It is as if being empowered through, and therefore more actively participating in the structures of U.S. state violence, white supremacy, and global economic and military dominance is something to be desired by Filipinos.

How could these acts of desiring what is in the colonizer’s economic and military interests, specifically on the part of Filipino elite, be explained? Especially when these colonizer interests run counter to their own?

Posted in colonialism/postcolonialism, Filipino Americans, Philippines | Leave a Comment »

Some things I’ve (re)learned from a year of riding.

The climb is its own reward:

That hubs are spaces of tension. (The graffiti on this one reads “Hike, not bike.” What does that make those of us who do both?)

Posted in outdoors | 4 Comments »

Posted in colonialism/postcolonialism, Philippines, race | 1 Comment »

In his

In his